Land & Legacy: A History

Nestled in South Bangalore between three major highways, Lalbagh Botanical Garden covers 240 acres of astounding tree diversity. In Hindustani languages, the name “Lalbagh” loosely translates to “beloved gardens”. It truly lives up to the name – the park is treasured by Bangloreans as a favourite spot for early morning exercise and a refuge from the hum of traffic.

Unsurprisingly, this garden hails from royalty. The layout of Lalbagh was first drawn out by Hyder Ali, an 18th century sultan of the Mysore Kingdom who acquired the land for private use. His son, Tipu Sultan, took up the task of adorning the gardens with its species. After his political visits, the Sultan would bring home countless exotic saplings, originating from the Middle East to Africa all the way to the Canary Islands. Indeed, we can thank Tipu Sultan for introducing the practice of horticulture to the garden and the region as a whole.

Lalbagh then went through the hands of various British superintendents, where it was valued for its use for food rather than its aesthetics or ornamental beauty. In 1958, nurseries and greenhouses were built within Lalbagh under superintendent William Kew, some of which still stand today. Embarking on the great potential he saw, Kew took to importing trees from South America and South-east Asia as well. Lalbagh was thus transformed from a private royal inheritance to a burgeoning site of scientific research.

Following Independence, Lalbagh passed under the jurisdiction of the Indian government and is currently managed under Karnataka’s Department of Horticulture.

Therefore, by the turn of the century Lalbagh had become a treasure cove of biological diversity. Sometimes affectioned the “jewel of Bangalore”, the extensive collection of tree species in Lalbagh continues to evolve and grow. From a selection almost 2,000 different species, native trees such as Peepal (Ficus religiosa), Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) and Champak (Magnolia champaca) line the pathways. In between these, introduced varieties such as the Baobabs from East Africa, Spanish Cedar (Cedrela odorata) and the tall New Caledonian Pines (Araucaria columnaris) have made their home. Through trade, politics and history, these complex trees now coexist to produce a novel ecosystem in Lalbagh.

The Purpose Behind our Tree Walks

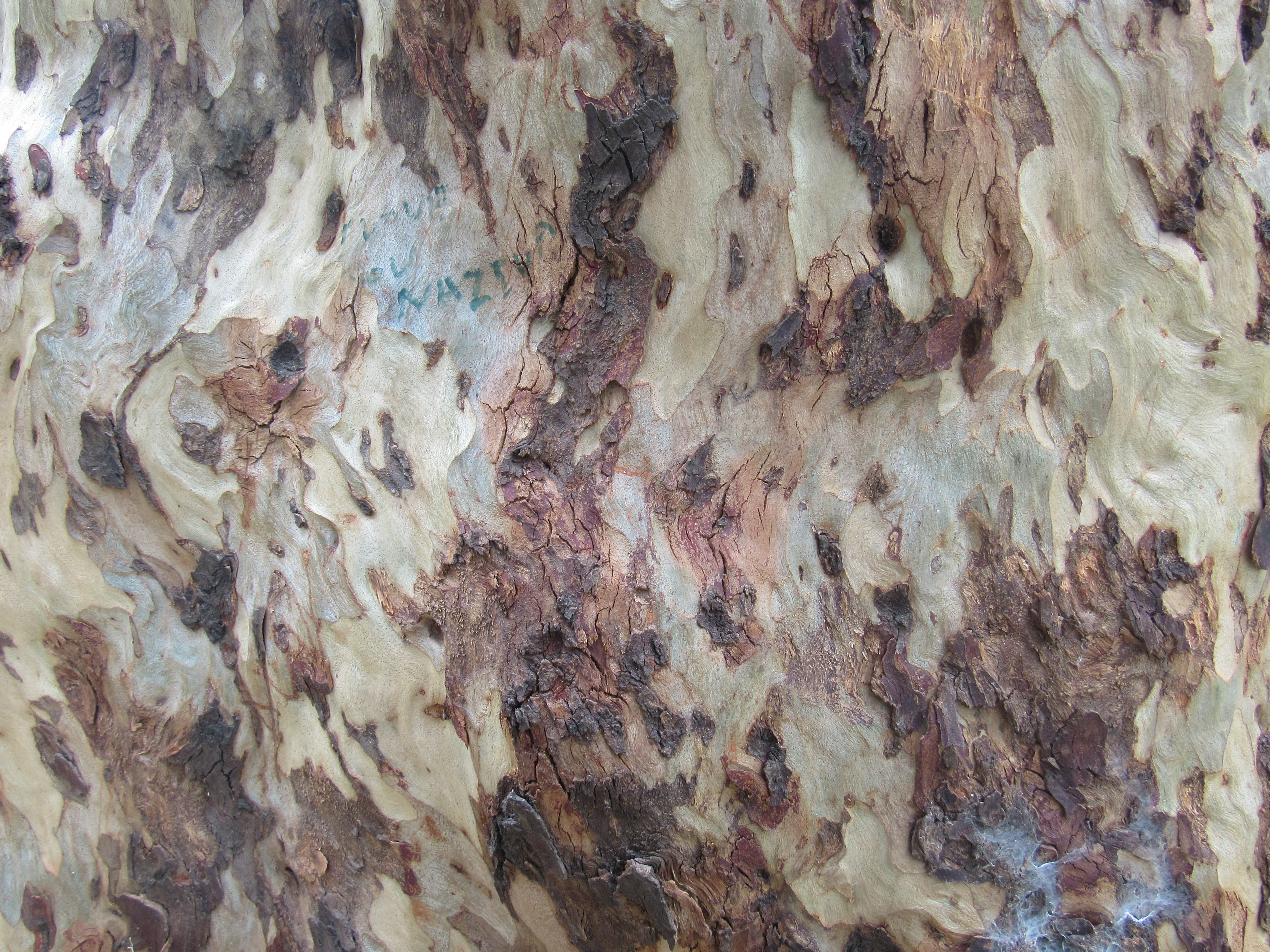

Here at a Green Venture, we conduct informational Tree Walks at green spaces around the city. Given its rich history, Lalbagh presents us with a unique opportunity to these witness majestic giants after more than a hundred years of growth. This is evident by their deeply textured bark, coloured trunks and far-reaching canopies.

Much like humans, trees in their old age come to look different than their younger counterparts, each taking on their own special characteristics. Take, for example, the species of Eucalyptus below.

Unlike the smooth, peeling bark of 30-40 year old Eucalyptus trees, this old giant has rough and undulating bark with a certain hardiness. It’s leaves extend far beyond our grasp, but give out a strong, sweet smell that reaches the ground.

Looks aside, the Tree Walk calls us to slow down and gaze upwards. We learn how to identify different tree crown shapes, from rounded to branched to columnar, and discuss differentiation between species by looking at leaf patterns, fruit and trunk.

Using these skills, we identify and talk of the history of each tree. We consider how the species have adapted to live in the current climate and support the animal biodiversity of the city. All the while, Indian palm squirrels flutter between our feet and a cacophony of bird calls accompanies us.

Here is a sample of some of the more eccentric tree species of Lalbagh:

Cannonball Tree (Couroupita guianensis)

Native to South America and the Carribean Islands, the scarlet flowers branching off the main trunk of this tree transform to “cannonball” fruits. As the name suggests, these rounded fruits are hard to miss – brown, woody and up to 25 cm in diameter. They hang off the tree for almost a year before falling to the ground with a crash. In stark contrast to its fragrant flowers, the cannonball fruit has a rather unpalatable smell. The pulp is nevertheless used by Amazonian tribes to treat various ailments and infections.

Elephant Ear Tree (Enterolobium cyclocarpum)

The national tree of Costa Rica, the Elephant Ear is known for its impressive size and dome-shaped crown. Amidst feathery leaves, its seed pods are also notorious for their ear-like shape. The pod casing is quite tough so it is difficult for these seeds to escape – a curious limitation to the trees’ reproductive capacity. In fact, to date, no animal is known to disperse the seeds of the Elephant Ear other than the prehistoric ground sloth. Interestingly, domestic cattle have come to the aid by crushing the pods with their hooves as they graze!

White Silk Cotton Tree (Ceiba Pentandra)

The crowned jewel of Lalbagh, a 250-year old Silk Cotton Tree rests near the west gate. It is the largest known specimen of the species in the world, spreading across almost 2,000 square metres in width and 17 metres in height. The branches spread out from its indentured buttress roots, creating the impression of a non-existent trunk.

By mid-summer, the pods of this tree burst open to disperse their seeds and reveal the soft white fibre within.

Beyond Lalbagh: The Future of Bangalore’s Trees

Lalbagh evidently represents many things at once – an impressive garden with trees that hold both history and beauty, a vital genetic resource from Bangalore’s ecological past, and a site of immense economic and therapeutic value.

We cannot forget that many of these tree species thrive outside of Lalbagh’s fences, lining our streets and enshrouding schools, places of worship and homes. As our city has developed, these trees have grown too, silently sequestering carbon, filtering pollution and providing much needed shade for the markets and businesses below. However, while the resident trees of Lalbagh remain in protected paradise, those outside are facing increasing threat.

A study at the Centre of Ecological Studies and Indian Institute of Science found that there was a 500% increase in concrete area in Bangalore in the past four decades. This was accompanied by an 80% decline in both vegetation and water bodies.

Across Bangalore old trees are now competing for light with the tall apartment buildings around them. But the issue is not development itself. The boom of the IT industry and influx of labour was met with unplanned and unrestricted urban growth. As Metro lines and road expansions took way, the oldest and biggest trees were marked as inevitable casualties.

The environmental benefits of large trees goes beyond our parks. Bangalore’s trees exist as a continuous canopy, creating a “green highway” for birds and small mammals to nest and hunt. This includes the Slender Loris (Loris lydekkerianus), a small nocturnal primate recently discovered to have adapted to the urban sprawl of Bangalore.

It is a push and pull. Whether for their sacrality or ecosystem services, a sizeable movement of citizens has sparked to speak against the felling of trees. This is an invitation to allow trees to once again shape the city landscape, and a call for public consultation before development plans are set in stone.

Hope is not lost to reclaim Bangalore’s title as the enamoured Garden City. Be it through Tree Walks or organized movements, a fostered awareness of these gentle giants are the steps forward to conserving our environment, history and health.

By Michelle Luiz

Join our Tree Walks held on Saturday mornings in the city, email a.green.venture101@gmail.com for details